History of Numbers.

Roman numbers.

Numbers 11 through 19

Numbers are everywhere, all around us. Why do we need numbers? How did people come up with the numbers we use today?

To help my 4-year-old child find answers to these questions, we completed several lessons dedicated to the history of numbers.

We learned how people first started using numbers. Long ago, when people needed to count things and make important choices, they came up with clever ways to keep track of the number of items, etc. They used methods like knots, rocks, seashells, and marks on sticks to help them count. This helped not only with counting but also with trading and measuring.

To make this even more fun, we gathered ten small rocks and played together. We added rocks and took some away. It helped us learn how numbers work, and we even discovered different ways to make numbers like 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 using those rocks.

Numeral systems

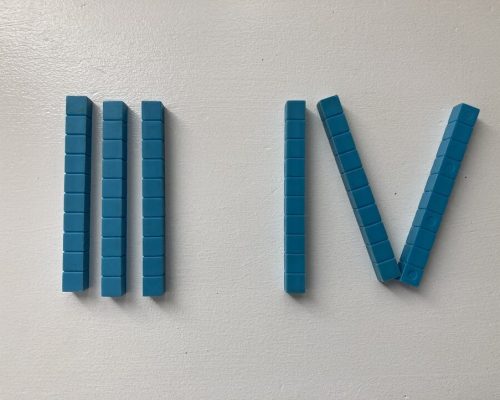

Once people learned how to count, they needed a method to write down these numbers. In the book “Learning Playground: Fun with Numbers,” we discovered that Europeans initially used the Roman numerical system, which was based on letters.

To remember the three main letters used to make Roman numbers from I to X, we visualized “I” as a stick or a finger.

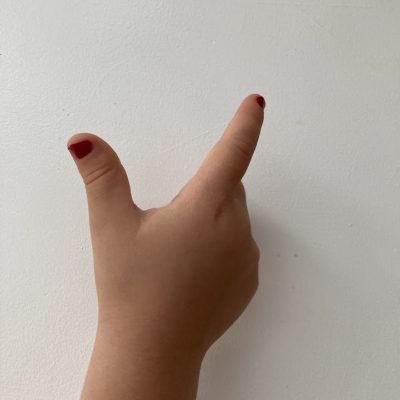

“V” looks like your hand (5 fingers), with the thumb extended:

To make “X,” you’ll require both hands (ten fingers) with pointing fingers crossing each other, like this:

We played with counting sticks, markers, and chopsticks to practice making Roman numbers from I to X.

Knowledge of Roman numbers came in handy when we made the Big Ben clock from the Kiwi Atlas Crate box. The numbers on the tower were Roman numbers.

We read that when Arabs conquered Spain, they played a significant role in spreading the Arabic numerical system throughout Europe. People found out that it was much easier to use Arabic numbers than Roman ones, and that’s why we use them now. I illustrated this to my daughter why, for example, you would write twenty-eight as 28 instead of XXVIII. She said definitely Arab numbers are definitely easier to write.

Numbers 11 through 19 mess.

I noticed that my daughter had a hard time counting out loud between 10 and 20. And I could see why. We count 1, 2, 3 … 10, and then instead of saying ‘ten-one’, or ‘ten-two’ and so on, we have these strange numbers eleven, twelve, then mixed up ‘three-ten,’ ‘four-ten,’ and so forth, before going back to a more regular pattern: ‘twenty-one,’ ‘twenty-two.’ Why do we have this unstructured approach?

It’s nice to be able to count, add, and subtract using the ten fingers on our hands. However, things can get a bit trickier when the numbers go beyond ten. I simplified the explanation for my 4-year-old daughter:

A long time ago, people were not very comfortable with numbers beyond ten. If someone brought 11 or 12 items to sell at the market, they had to count them. To make it easier, they came up with names like ‘one-left-over-ten’ and ‘two-left-over-ten,’ which we now know as eleven and twelve. These names stuck in the English language, and nobody changed them.

I didn’t delve into the explanation of the influence of the Anglo-Saxons on the modern English language. Instead, I simplified it to the idea that a long time ago, people needed to name numbers beyond 12, and the German people already had names for these numbers. They borrowed the idea of naming from the Germans.

In German, numbers are written left to right, but they are pronounced right to left. For instance, ’15’ is pronounced as ‘Five and ten,’ and so on.

So, for numbers 13 to 19, the English language has adopted a German-like approach to naming. In addition, instead of using the regular word ‘ten,’ we have a modified word ‘teen’ derived from an old English word. After the “teens”, we use the regular way of saying numbers from 20 onward, left to right.

I noticed that this simplified explanation was helpful, and my daughter became more comfortable with numbers 11 through 19. As a result, we were able to move on to addition and subtraction beyond 10.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.